If you were limited to choosing just one plugin to use exclusively for the rest of your production career, EQ would be among the wisest ones to pick. EQ, or equalizer, is a powerful tool with realms of diverse production options – not least its use in EQ’ing orchestral instruments – but often overlooked or misunderstood by less experienced film and game composers.

In the following tutorial, we’ll look at some general tips for applying EQ to each of the four orchestral instrument families that will provide a starting point for you to accentuate certain characteristics of your instruments and give your composing a voice. Just like with any good tool, the only way to get a really good understanding of your EQ plugin is to spend some time tweaking it.

What is EQ Used for?

EQ’s most basic function is to cut or boost certain frequencies relative to each other, giving you a lot of control over how your mix ends up sounding – in other words, it’s like a sophisticated version of the treble and bass controls on your stereo.

Having invested in a good orchestral sample library with a plethora of sounds, you’ll be anxious to get composing. Modern sample libraries are extremely good at producing “out-of-the-box” instruments. In other words, most of the samples you use will already be EQ’d to a generally good standard. This is particularly true if you purchased an all-in-one sample library package rather than buying different instrument groups individually. However, EQ can and should still be used to enhance and add realism to your orchestral MIDI mockups.

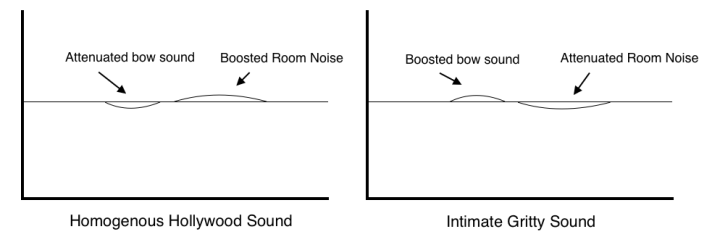

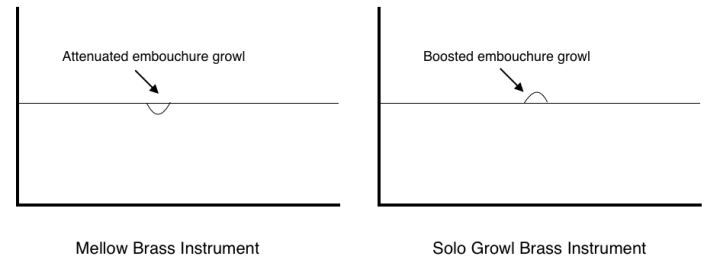

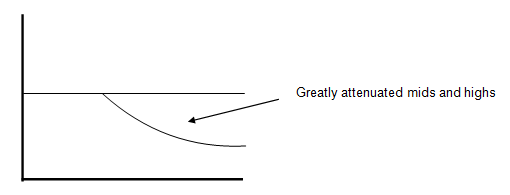

For this tutorial, I’ll be assuming a basic knowledge of what an EQ plugin is and how it is used. The images I’ve provided here are not to scale, as specifying exact frequencies for every sample library would be impossible, but they will provide a nice visual starting point for you to replicate and tweak as necessary.

Let’s get right into it!

EQ Tips for Strings

Let’s imagine two different string recording scenarios. First, we have a large string section that is recorded using overhead mics from a relatively distant location. Second, we have a string quartet with each instrument mic’d up very closely. Both are very different string sounds that have their own merits in different situations. The first would be associated with that Hollywood “soaring strings” homogenous sound, whereas the second is much more intimate, with the details of each instrument easily heard. We can use EQ to accentuate certain features of each of these examples.

The first recording of the large string section is likely to contain more room noise than the second recording. Therefore, if you locate the frequencies of the room reflections in your own samples and boost them, you can get closer to recreating that homogenous Hollywood experience.

Conversely, the second recording of the string quartet is likely to contain the gritty textures that occur as the bow passes over the string, which are particularly audible when the performer is using the frog of the bow. These nuances would never be picked up in the first recording, so boosting them in your own samples can create the illusion of a close-mic’d, intimate string sound.

EQ Tips for Brass

Brass instruments can be difficult to work with regarding EQ; this is because they typically take up a very large frequency range. However, they are also quite malleable. Due to the almost abstract nature of the brass sound, you’d be surprised how much you can edit the EQ of a brass sample while still keeping it sounding perfectly legitimate.

So, if you need to create some room for another instrument section to punch through, don’t rule out brass, because they are likely to be able to withstand a cut in a certain frequency range more than other families. A great demonstration of this would be the brass theme from The Matrix. Highly edited using EQ, yet still undeniably brass.

Try also experimenting with the “bite” of brass instruments. The trump-like growl that features in some styles of playing is completely different to the more mellow performance of others. Locate the frequency of these growls, and then boost or attenuate them to suit your needs.

EQ Tips for Woodwinds

In contrast to brass, woodwind instruments are typically less resilient to heavy EQ’ing, so a delicate touch is required here. Anything more than that is likely to make your woodwinds sound more like general MIDI than the high-quality samples you paid for.

Woodwind instruments also operate in a relatively narrow frequency range, so making room for them in the mix isn’t too tricky and they should be pretty good at blending in out the box.

I’d like to point out one feature of woodwind instruments that, when boosted, can really add character to your samples. That feature is the fingering. This is a very nuanced EQ technique with extremely subtle results, so I would recommend using it for solo woodwind instruments that are the focal point of the music.

Let’s take a flute as an example. As the flautist presses the keys of the instrument, this creates a percussive sound. If enough air is being blown through the instrument as this happens, then you get a rather nice-sounding “pop” sound.

Contemporary composers have taken advantage of this technique and even written whole pieces around this acoustic phenomenon. While you may not want to go as far as that with your own compositions, boosting the frequency of the keys being pressed adds a fantastic level of detail to your samples. I would liken this technique to when pianists in pop albums purposely mic up the piano stall because they feel that the creaking adds character to the recording.

EQ Tips for Percussion

The percussion section is where you have most creative freedom regarding EQ, and it’s a great place to get started tweaking. In many ways, anything goes!

Let me clarify – if you’re looking to replicate a percussion instrument very accurately (a roto tom, for example), then of course over-the-top EQ’ing is going to prevent you from doing this. But the nature of percussion is such that instruments don’t have to be replicated accurately to sound fantastic (white noise is often used to create snare hits, for example). Allowing yourself to create more abstract percussion sounds using EQ can (as long as your composition isn’t for live performers) give it a very unique flavor.

Let’s take a taiko bass drum for example. This magnificent instrument is one of the deepest instruments the percussion section has to offer. If it’s bass you’re after, you could consider using quite intrusive EQ’ing to accentuate this.

In the example above, only the bass frequencies will be punching through. Now let me be clear: This will definitely not sound like a taiko bass drum. So if that’s your aim, then EQ’ing in this fashion is a bad idea. But if you’re simply looking for a percussive gesture, then don’t be afraid to really step in and make some changes to the sound. In this example, the lack of mids and highs could be complemented with another instrument. Have fun combining instruments of different frequency ranges to create a truly unique percussive sound.

The secret of EQ’ing orchestral instruments well is knowing when to be bold and when to be delicate. This knowledge only comes with experience and practice, so my word of advice is to experiment.

Featured image by Chad Kainz

Do you have any useful tips or tricks for EQ’ing virtual instruments for film and game composers? Share them in the comments!

Thanks for the article. Any tip helps.

However, the problem with high strings hasn’t been solved till these days. Their equalization if fraught with enormous harmonic problems that are inbuilt to begin with. IMHO, there’s no best string library out there because they all have the same problem, namely, a suite of very high harmonics that cannot be cut without substantially, if not totally, altering their tone color. In fact, one is left with a synthy kernel, surrounded by a haze of white noise that I call sand paper effect (in German the term would be Schmirgelklang). If one only filters these parasitic noises (which are at the origin of grittiness), then one ends up with, well, gritty, discontinuous, uneven, sound. Some people equate this noise with bow noise, which I think is a mistake. For this reason I could not produce sweeping, dramatic melodic lines with high strings. I mainly write these kinds of lines, and invariably end up with bad sound. And, yes, the strings ARE in a much higher harmonic register compared to the underlining harmonic structure. Surely, one can write those minimalist ostinatos that pervade most all action scenes in that relentless, never changing E minor key, adorned with all of the articulations in this world. My purpose though is to write song-like lines. That’s hardly possible with the current libraries offered throughout the industry.

We’re constantly talking about mockups. Well, if we insist on using this term, then we’ll always get mockup quality samples. Why should manufacturers strive if there’s no demand for, yes, quality samples? Surely, from time to time, with great hype and exaggerated claims, industry will come up with new versions of their libraries. But, time and time again, I end up getting that bitter taste of raisin bran marketing theory. What did I just say? Well, sometime in the early ’90s, industry maven Louis Gerstner, then CEO of IBM, was answering questions at a press conference. He came from the cereal industry and answered the question in those terms. I cannot quote him exactly, but he said something like this: Now I am in the computer industry. It’s crazy. The rhythm of development and competition is absolutely maddening. When I was in cereal manufacturing, we put 4-5 raisins into a box and declared the product “new and improved”. You cannot do this in the computer industry. You’d sink in a heart beat.” Let me use this example as an analogy. I dare say that sample manufacturers kind of do the same thing. They build 4-5 new articulations into the library and declared it a new version. However, sound quality (I am talking here about high strings, the weakest link in general as far as string libraries are concerned) is hardly changed. This is the crux of the problem, IMHO.

Thanks for reading, J.

Sorry for having been somewhat imprecise. In my example, I am talking about the cereal “Raisin Bran”. So it’s 4-5 more raisins and NOT just 4-5 raisins. Correction necessary. J.

As a sound designer, i know what are you talking about.

1,The high gritty sound usually a chain reaction build up.. Many sampling engineers are not good recording engineers. They even have very low level sounding rooms and speakers.

2, Using bad digital eq-s in kontakt libraries, they try to make it sounding better but it ending with digital shizzle. So turn them of.

3. Try using low pass filters extensively on every sounds. The vintage samplers of sampling art was the low pass filter, and the nice dynamics. The ear does not like dry stuff loud above 10-15khz.