The proper application of MIDI continuous controllers is just one topic of study that falls under the broader category of MIDI orchestration techniques. In a nutshell, MIDI continuous controllers — a.k.a. CCs — are a type of MIDI message that can be programmed across a range of values, most commonly from 0-127.

While a lot more can be said about continuous controllers and MIDI in general, we’re going to look at three of the most important CCs for film and game composers from a MIDI orchestration standpoint: CC#1 (modulation), CC#7 (volume), and CC#11 (expression).

Along with velocity (which is not a CC), skilled producers apply CC data to MIDI mockups to emulate a live orchestral performance as closely as possible — from changes in timbre and dynamics to playing techniques such as vibrato. Learning how to handle these parameters is one of the most vital MIDI orchestration techniques a film composer can learn.

CC#1 — Modulation

Modulation is one of the most commonly used continuous controllers — so common, in fact, that most MIDI keyboards contain a mod wheel to control this parameter. This CC value is often assigned to various controls, but the standard operation is to add vibrato to the sounding notes.

If you’re a classically trained musician, don’t confuse the meaning of the word: “Modulation” in this sense has nothing to do with a key change as it does in music theory; rather, it refers to the rapid alteration of pitch around a base note.

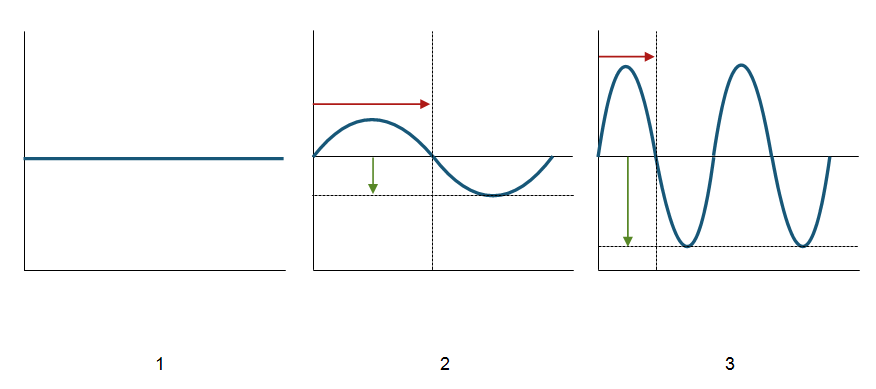

Increasing the modulation parameters of a note changes two key things about its characteristics. In the following illustration, the X axis represents time, the Y axis represents pitch, and the blue line represents the note.

In the first diagram, we can see that as time goes by the pitch does not vary at all. This note has no modulation applied to it.

In the second diagram, the pitch changes, or modulates, up and down over time. This is the effect of modulation. The pitch varies around the original (static) frequency.

As the level of modulation increases in diagram 3, we notice two things. Firstly, the amount that the pitch varies has increased, as can be seen by comparing the two green arrows. And secondly, the rate at which the pitch varies has increased, shown as the difference in the lengths of the red arrows.

This is all very well, but how is modulation used in a practical sense? For one, it can be used to add flavor to your synth melodies. Using excessive modulation on harmonies can often produce dissonant chords. Depending on the effect you’re going for, this may or may not be a bad thing.

More commonly, adding modulation to just a few crucial notes rather than the entire melody is used to add variation to a synth track. Modulation works well on longer, emphasized notes; for instance, at the end of a melodic passage. I recommend giving “The Tip of the Iceberg” by Owl City a listen, as it demonstrates this point perfectly.

In a MIDI orchestration scenario, many high-quality orchestral samples are configured to change timbre as modulation is applied, emulating the sound of vibrato being played by a real musician. This is a very effective way to add realism to MIDI mockups, particularly if the modulation data is recorded in real time using a breath controller or slider on your MIDI keyboard controller.

CC#7 (Volume) vs. Velocity

CC#7 controls a parameter that we are all familiar with: volume. While volume refers strictly to amplitude, which is an objective measurement, it’s often used interchangeably with “loudness,” which is a more subjective notion. CC#7 should typically be set at the beginning of the track and left alone.

It’s important to note that volume is not the same as velocity.

To clarify, imagine that you’re composing an orchestral track for a battle scene in a film or video game. You play in a melody on an 18-violin patch, but upon playback you realized you played it in too softly — it’s missing the “bite” characteristic of an action sequence.

At this point, you might try to turn up the gain, but it still doesn’t produce the result you were hoping for. The reason for this is because you have only increased the amplitude, which has no effect on the sample’s resultant timbre.

Playing in a note softly will trigger a sample that was recorded softly. By increasing the volume, all you get is a very loud version of a quiet performance.

To really add oomph to your tracks, edit the velocities in proportion to the type of performance you want. For softly played passages, don’t just turn the volume down — decrease the velocity. For bold passages, don’t simply increase the volume — increase the velocity as well.

Looked at another way, the velocity allows you to control the way a sample is articulated.

CC#11 — Expression

It’s important to note that both CC#7 and CC#11 control loudness. This often leads to some confusion.

Think of these two parameters as being different in application. As noted above, CC#7 is typically set at the beginning of the track and left alone. Use CC#11 to control volume changes during the track.

As an analogy, imagine a guitarist on stage. Her electric guitar is plugged into an amplifier, which has a set volume throughout the entire performance — this is representative of CC#7. As the guitarist performs, she plucks certain notes harder than others, allowing the volume to swell up and down throughout the performance — this is representative of CC#11.

CC#11 is usually controlled using an expression pedal. This allows the composer to control swells in volume with his or her foot.

CCs 1, 7, and 11 can be used in conjunction with other sequencing techniques to really enhance the dynamism and realism of your MIDI performances. Learn to use them well!

Featured image by Katie Wardrobe

At last, somebody who has explained exactly what CC messages do, and more importantly what effect they have on the music.